In terms of sonic and emotional impact, how do you make the decision between Spanish and English?

I had the blessing of encountering the poetry of Reyes Ramirez in the summer of 2017, and I remember thinking, damn, I don’t even want to call this codeswitching. His movement between languages felt so fluid and natural, they felt like the same language for me. Most of my choices about language are intuitive and I strive for the fluency I found in Ramirez’s work. That is not to say that the choice is solely grounded in my unconscious or my gut. In “Tia Tere as Sipakti Talteguyu,” I chose to have the deity speak specifically in Spanish because that act of exclusion felt divine. You must know Spanish in order to hear the voice of God in my poems. For the Spanish translation, I recruited Petrona Xemi Tapepechul to translate the voice of God into nawat, one of the most common indigenous tongues of El Salvador.

Have your mother and family members read the manuscript and what are their thoughts on it? How do you handle the responsibility of representing their stories in such a graceful way?

I am blessed and cursed with the fact that most of my family does not read English or is uninterested in poetry. It’s a blessing because I’m freed from the fear of their judgment, which at least in the draft stages is important not to paralyze my voice; later on, it becomes a curse because I need to translate what I wrote into Spanish, my less dominant tongue. It’s a curse because I feel like I can’t share my work adequately with the people I love most. It’s a curse because their experiences are in Spanish, so I’m in constant translation. It’s a blessing, however, because the poems have given me the space to open conversations that never would have otherwise happened. Poetry has made it possible for my loved ones to open up about these details and me to reflect it back to them in a loving way.

A lot of heritage speakers of English struggle with poetry. On top of the challenges of the genre in general, my parents are only semi-literate in English and Spanish. For years, my mother and other family members had zero access to my poetry. That said, I tried to have conversations with my mom about every poem in the manuscript. She had interesting feedback here and there—details to include, what to omit.

Photo of Willy Palomo reading at V Festival Internacional de Poesia Amada Libertad in El Salvador. Photo from Inger-Mari Aikio’s Facebook profile.

I had the blessing of taking my mother with me to El Salvador summer 2018, and she was there for the V Festival Internacional de Poesía Amada Libertad. For the Festival, I read to Spanish-speaking audiences and was forced to translate three of my poems. Until then, I hadn’t translated my poems in fear that they would suck. But the only thing shittier than poorly translated poems is poems in a language the audience can’t even understand. I started translating my poems thanks to the encouragement of Alberto Serrano Lopez, Jorge Lopez, Josués Andrés Moz, and especially Claudia Flores. I feel immensely blessed that the first time my mother heard my poetry about her it was in her native tongue in her homeland. She wept as I read “Witness” and “Where we see Mama’s back.”

I attempted to translate the book by myself, but every native Spanish speaker I consulted told me the translations had to be redone. I’m grateful for Alejandro Garzón and Josué Andrés Moz’s weeks of work spent toiling over every word in the manuscript to translate it to a rhythmic and direct Spanish. The one poem I completely translated myself is “How I learned to read,” an abcedarian, a form my translators either missed or didn’t attempt to replicate. They made minor tweaks to the translation and ultimately valued my commitment to the form.

The availability of the poems in Spanish, of course, created vulnerability for me, as my parents and relatives discussed sometimes contested memories. Some of them, it seems, are particularly invested in testing the veracity of my storytelling against their own memories and perceptions. So far, however, my years of work have paid off. Since poetry is a work of art, many are willing to accept the creative liberties where I took them and sometimes even consider genuine differences in perception of a situation as a “creative liberty.” I have no qualms in admitting some family members aren’t portrayed in the best light in the collection, but I firmly committed to representing my mother’s perspective first and foremost in the book and have zero regrets about that. My reading with Casa de La Cultura El Salvador had over 550 people present and was a dream come true. My parents have wept during live and virtual readings of my work in English and Spanish. My mother read the book more or less in one sitting and sent me a message afterwards I will cherish forever. I was shook when my thirteen-year-old niece sent me text messages after she finished the book expressing how transformative of an experience it was. These moments of connection with my family are more valuable to me than any literary magazine acceptance or award, and I am in awe that my work managed to bridge such disparate audiences. It was one of the hardest challenges of the book: how to write something that my family, youngsters, and spoken word communities can appreciate and that is still publishable in reputable literary magazines. It was a tremendous strain to write under, and I am surprised I had as much success as I have had.

Do you consider it is possible to heal intergenerational trauma or at least begin to understand it by examining the past through an artform like poetry?

Poetry is literally just talking carefully. I believe it is probably impossible to heal intergenerational trauma without talking about it at all. Many of the best poets I know write to break the silences that harm us. Many of the children of Salvadoran refugees grew up in households with lots of silence about the war and our culture and in educational communities that erase our histories.

There’s a poem, “Where We Find Mama’s Tongue,” where I talk about an experience I had the first time I went to El Salvador at age eighteen. As we were getting ready to go to sleep, I asked my mom why she never told me about El Salvador. She didn’t even answer me. A year later, I reminded her about the question I asked and she said, she couldn’t respond because she felt a huge knot in her throat and tears welled up in her eyes. My tia Morena asked me, how could you expect your mom to translate this entire country and everything we experienced to you? A lot of my book came from my personal need to understand El Salvador and what my family underwent. It has been immensely healing for me in some ways to bear witness to my mother’s stories and preserve them.

I don’t know if intergenerational healing is possible through poetry—the idea sounds too romantic to me—but the poems I have seen come closest to what feels like healing are Janel Pineda’s “In Another Life” and Yesika Salgado’s “Hermosa.” It’s not the idea that poetry can be healing that is suspect to me, however; it’s the idea that healing is ever possible or desirable that is most suspect to me. We live in culture that currently obsesses with trauma while also being pretty traumatophobic. Here, I don’t use that term in the medical sense, but in the sense that psychoanalyst scholar Avgi Saketopoulou uses it. She uses traumatophobia to talk about the way people treat trauma as a thing to be battled and overcome, usually in a pretty linear fashion. This idea does violence to us in two big ways; firstly by giving us the false impression that healing significant traumas is even possible, and secondly, by convincing us that it is even desirable. She contrasts traumatophobia with traumatophilia, where rather than trying to eradicate a trauma, the traumatized learn to tend to their griefs, their angers, their turmoils, and to build healthier relationships with them, which frequently means revisiting the trauma in new contexts rather than merely repressing it. Poetry, at its very best, can be part of someone’s restorative approach to trauma, but I doubt it or anything else will save us from our traumas. I only speak for myself, but at this point in my life, I’m not sure if I even want to be saved from it.

Do you feel that poetry has any power to affect real change? And do you think that all poets have a responsibility to be engaged with the world in a political way? What do you think of the notion of the "personal as political?"

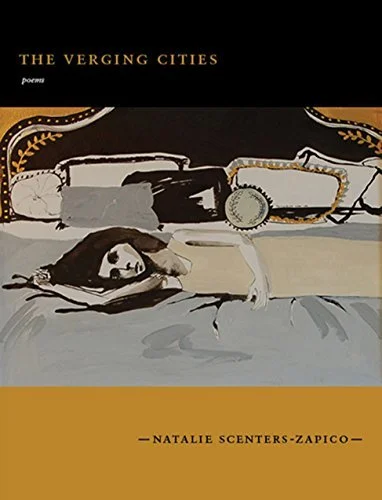

I think everyone of all walks of life have the responsibility to minimize harm and maximize the health of all life with which we share this planet. This will inevitably involve politics for most people. I believe poetry can save lives, because I’ve witnessed it do so too many times. I believe poetry can create change, because I’ve literally sat in activist group meetings and asked people why they showed up and they referenced the poetry of Marcelo Hernandez Castillo, Natalie Scenters Zapico, Christopher Soto, and others. Who was it that said art should disturb the comfortable and comfort the disturbed? It’ll take a lot more than poetry to save us from our contemporary political crises, but without it, a number of wonderful people I know would no longer be with us.

The personal is political because QPOCs’ lives have been politicized to the point that nothing seems to belong to us anymore. Who I fuck is personal. Whether I feel more comfortable in a dress or in a tie is personal. My choice to love my undocumented friends, partners, and family is personal. My family’s experiences of war and migration are deeply personal. But each of these things is also politicized by people trying to do my communities harm; I doubt my communities would politicize these aspects of their experience if they did not have to. As writers, its our job to protect our narratives from being misread, and that means being aware of the ways they may be politicized. Right now, I’m at a point where carving out space for what is sacred to me and only me and my kin is my primary concern. Everything can be political and I am trying to be conscious about politicizing my stories only when it seems necessary to comfort and/or defend my communities. In my opinion, politicizing the personal becomes necessary far too often. I rather live in a world where what’s personal to me can stay that way.

You have a very accomplished background in slam poetry, performing nationally and internationally at National Poetry Slam, CUPSI, and V Festival Internacional de Poesia Amada Libertad in El Salvador. There are still misperceptions about slam in the academic and publishing side of poetry. Have you experienced any of that in going from doing slams to publishing on the page? Do you feel that there are adjustments that must be made when your piece goes from being read out loud, to being read on the page?

Slam is a whole can of worms, because its practice varies from scene to scene and oftentimes, it is equal parts an empowering training ground and workshop for writers of all experience levels, as it is a limiting, toxic, and impoverished way of looking at art. It’s a capitalist reduction to art as a competitive experience that can be reduced to numbers, and yet that competitive framework has allowed alternative, LGBTQ+, and BIPOC styles to flourish, especially because the publishing and academic industries are in many ways feudal and nepotistic. At its best, it’s a community of creatives who do not care for the results of the competition but use the medium to take risks and create experiences that strengthen the bonds of community.

The question and problem you posed, however, used to plague me during my undergraduate studies, but I mostly considerate myself past these concerns now. As a youth poet, I was insecure about the way my spoken word would be received in academia. I had a pretty toxic set of poetry mentors coming up with the exception of Jesse Parent, one of the slam veterans of SLC. Most of my challenges came from the fact my white mentors could not, despite their expertise, help me understand who I wanted and needed to become. I was a young Salvi without a proper understanding of my cultural heritage, my queerness, without an understanding of how growing up in a predominantly white Mormon society warped my views on gender, sexuality, and race. They didn’t understand POC spoken word traditions and used to shame me for drawing from hip-hop and Nuyorican traditions. The biggest challenge was learning how to negotiate the relationship between the stage and the page. Because I didn’t understand enjambments or form quite yet, some of my mentors would treat my spoken word techniques as an impediment, rather than a strength, rather than teaching me how to translate my sonics-driven poetry to the page. Of course, the stage and page are different, but when I was young, I would push back and claim they should be the same. I think I did that because I feared that if the stage and page were different than my mentors’ criticisms of spoken word poetry were valid; I definitely did that because many poets who have a disdain for spoken word also have no sense for sound and rhythm themselves.

But of course, there are opportunities on stage that don’t exist on the page and opportunities on the page that don’t exist on the stage. I think it all changed for me when I started thinking of so-called page poetry as visual art. I strive to make form match content match performance. I think the best poetry is a marriage of the three. I think there’s some jaw-dropping poems that can’t be translated from the stage to page and vice versa.

Can you speak to the way the religious or the biblical has had an impact on how you construct language?

I spent the first seventeen or so years of my life as a devout, practicing Mormon and the next four or so years transitioning away from the church. I first learned to close read and critically analyze texts by studying symbolism and narrative in scripture. Mormonism gave me the soulpain and the toolset that made me a poet. Scriptures once wracked me with guilt almost to the point of suicide. Prayer and scripture also saved me from darkness. I developed an unbridled, at times irreverent style of prayer inspired by D&C 50:12, which encourages people to speak to God as you would speak to anyone else. This approach worked for me, giving me experiences I still sometimes call revelation. My poems are oftentimes prayers, a way of crying out to God and listening to what echoes back. Sometimes my poems are prayers. Sometimes my poems are responses.

Your work often feels as though it communes across realms and through different time-periods. Who would you say your work speaks to most now and then, dead and alive?

I believe the spirits of our ancestors and descendants guard and inspire us as long as we honor them and honor ourselves. It is beautiful for me to think that my great grandmother, who once saved my mother from death and illness as a baby, is also fighting to save me. That my future son could be the one who pushes me beyond fear and submission. That I could have been with my mom during the war, at the border, etc. We’re all in this together. Wake the Others tries to unite the dead, the alive, and the not-yet-born. I want the next generation to have access to our family’s stories. I want my ancestors’ struggles preserved in the best words I can give them. Because we need each other. Because we will need each other again.