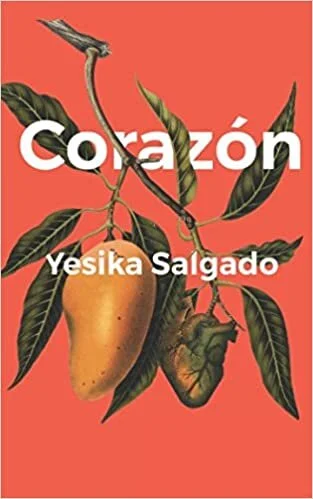

Corazón / Yesika Salgado / Not a Cult Press / October 2017

Peluda / Melissa Lozada-Oliva / Button Poetry / September 2017

Corazones Peludas: Two Gorgeous Poetry Collections by Centroamericanas

Imagine you are at a slumber party with all of your homegirls, complete with nail polish and cheap booze. Your homegirls give you two options: Would you rather be 1) “completely covered in fur, like, head-to-toe, monster type of shit,” or 2) “perfectly smoothie-smooth in all of the right places: thighs, crotch, armpits, upper lip, neck? But here is the caveat, alright: all of the hair that would have grown in those places takes the form of a tail.”

Melissa Lozada-Oliva poses the reader this question and many more in her debut collection of poetry, Peluda (Button Poetry, 2017). On the front cover, the nightmarish image of Lozada-Oliva’s slumber party monster repeats on a daffodil-yellow background. If this hairy monster is comical or absurd, it is also an accurate portrayal of the monstrous ways American culture distorts the bodies of women who fail to uphold its rigid guidelines. The hairy monster is an externalization that perfectly symbolizes the anxieties many Latinas face. At the end of the slumber party poem, the speaker’s woke friends dismiss her party question, focusing instead on self-love and acceptance of their body hair; meanwhile, the speaker confesses, “I always choose the tail,” a heartbreaking, if silly conclusion to the game. Lozada-Oliva’s ability to balance whimsical humor with breathtaking disclosure is what makes her poems so magical. Lozada-Oliva deftly navigates Latina identity with a brutal playfulness, an undeniably addictive rhythm and punctuation that squeals and screams, giggles and sobs off the page.

As if in call-and-response to Peluda, Yesika Salgado published Corazón (Not A Cult, 2017), her debut collection of poetry. Corazón chronicles the poet’s journey through heartbreak and romance to self-love. Whereas Lozada-Oliva’s voice is unapologetically girly and visceral, Salgado strikes the page with a gut-dropping honesty and introspection. I am not sure how exactly Salgado would respond to Lozada-Oliva’s slumber party question, but in Salgado’s poem, aptly titled “Peluda,” she reveals the way our culture’s policing of hair has infected her relationships:

I used to leave your house before we fell asleep / tell you I had to get home before work the next morning…

The night sprawled out before me as I made my way home / to the razor blade in my shower / the hair on my chin growing / a hundred little fingers ready to give me away / ready to show you I am not the woman you think I am / that sometimes I am grizzly / manic / human

one day / I didn’t leave / you said love / I believed it / the sun found me and my bearded chin in your kitchen / stirring oatmeal / your hands on my waist / a soft song saying / so this is what it means to stay

Salgado’s poems have the preternatural ability of capturing the smallest domestic moments and excavating their emotional core. Her poems demonstrate the power of vulnerability, its ability to make love possible and heal wounds.

Peluda and Corazón are both poetry collections by Latinas whose bodies are under intense scrutiny—for their color, for their hair, for their size. They plunge their reader through the conundrums of contemporary Latina identity, a maze of mirrors where the authors’ immigrant heritage and self-perception are disfigured by the male gaze and xenophobia in America. A side-by-side reading of these collections reveals not only the common struggles shared by these two young Latina writers, but also the complimentary, if at times opposing, strategies for coping with the pressures of America’s beauty standards. In a culture that attempts to reduce Latinas to housekeepers and sexual objects, Melissa Lozada-Oliva and Yesika Salgado write poetry that demonstrates the complexity and range of Latina identity in the 21st century. Far from the flat portrayals of pan-Latino characters common in the mainstream, Lozada-Oliva (a Guatemalan-Columbian American) and Salgado (a Salvadoran American) unflinchingly unpack their fraught relationships to their Latinx backgrounds, to their bodies, and to men.

Both poets pay special attention to the ways destructive behaviors are passed down one generation to the next. In these moments, they reveal intergenerational trauma and reveal the work it takes to heal. In “Traditions,” Yesika Salgado parallels her mother’s response to her father’s misdeeds to her own response to her partner’s misbehaviors. When their men ask questions stemming from insecurity and guilt—such as “we are happy, aren’t we?” or “you’ve forgiven me, right?”—both Salgado and her mother fail to rebuke them or respond frankly. Rather than tell the men “the everything of everything,” Salgado responds with a tearful nod. The love and commitment Salgado and her mother have for their men overpowers their need to hold them accountable in this moment. The moment is filled with risk: Do I suffer in silence or do I upset this gentle moment? Can I let go of my hurt and resentment? Will things work out? Fear of the unknown, of loneliness, of being unloved, of fighting again and worse charges these pages with an explosive energy. In “Traditions,” Salgado chooses the path of her mother and refuses to spark the fuse—for now. The poem raises questions about the soundness of this choice, foreshadowing the rise of a speaker who will soon find her strength to demand more from her partners.

In “I Shave My Sister’s Back Before Prom,” on the other hand, Lozada-Oliva describes how her sisters inherited hair from their father and fear from their mother. Here, the father not only works with the mother to police their appearance and behavior, he also gives them the physical trait that prevents them from fitting in. “maybe this has always been about our parents & all the things we never told them & all the ways they made us different,” Lozada-Oliva laments before shaving her sister’s back. Shaving, in the poem, becomes a celebrated act of rebellion, paralleled with their sneaky choice to stay up past their curfew.

Beauty routines accrue meaning throughout Peluda until they ultimately become redefined as acts of resistance. This move is crystallized in the last poem “Yosra Strings Off My Mustache Two Days After the Election in a Harvard Square Bathroom,” where the speaker declares,

this isn’t oppression. this is, i got you.

i believe you. it hurts but what else are we going to do

it aches but we have no other choice do we

Beauty routines become rituals of love and self-love, where community and support are found. Lozada-Oliva knows she cannot escape oppression. She cannot heal all the wounds. The years of shame cannot be undone, but throughout Peluda, Lozada-Oliva overcomes shame by outperforming it, by beating it at its own game.

If Lozada-Oliva and Salgado appear to be obsessed with hair, this compulsion is the result of living in communities so ready to attack them for any stray strand. In Salgado’s “Hair,” for example, the poet remembers, “you’d complain / about my hair. / how you always / found it in my sheets / after I’d gone home.” Stray hairs are often viewed as disgusting or annoying, but in the post-break-up phase of “Hair,” where the poet is suspicious of their ex’s infidelity, hair also becomes evidence of their relationship, and in turn, possible evidence of an affair to another woman. This realization raises suspicions about the motive behind the ex’s complaint, compounding the emotional weight granted to stray hairs.

Similarly, in “My Hair Stays on Your Pillow Like a Question Mark,” a white girl (Lozada-Oliva’s phrase, not mine) criticizes the speaker for leaving behind hair at her apartment. Almost the entire poem is end-stopped with double question marks, signaling the insecurity sparked by the white girl’s criticism and littering the poem all over with hair. Hair, as we know from “I Shave My Sister’s Back Before Prom,” becomes a symbol of Lozada-Oliva’s heritage, so in the poem, the white girl’s disgusts makes Lozada-Oliva insecure not just about her appearance, but her heritage:

imagine your hairs as daddy longlegs

crawling up the shower curtain??

daddy’s long legs??

daddy’s dark legs??

daddy’s hairy dark legs??

imagine you are what makes the white girls in a brooklyn

apartment scream??

except deep down?? you want to be a white girl

in a brooklyn apartment??

In these poems, hair has the power to define and literally create its bearers. Here, it transforms Lozada-Oliva into a spider, then her father, both of whom are terrifying and inhuman to the white girl in Brooklyn.

Like their relationships to their hair, their relationships with their homelands are equally fraught. In “Jenny and I” and “My Salvadoran Heart,” Salgado pushes past the clichés of homeland nostalgia to create a striking parallel between her longing for a homeland and her longing for a lover. As the first two poems of the collection, these poems become a sort of ars poetica, a map with which to read the poet’s journey through love and heartbreak. In “Jenny and I,” the mango is established as a place marker for El Salvador, and El Salvador is described romantically as “that country we considered wild / all that green / all those animals.” Salgado’s front cover, designed by Cassidy Tier, shows a heart growing beside a mango on the same branch. For Salgado, “love” is “a dangling fruit I ached to eat.” Similarly, in “My Salvadoran Heart,” Salgado tells us,

I am asked if I want a husband / asked if I will return to my country / they are the same question / I do not want to answer.

The conglomeration of romantic and diasporic longing makes each of Salgado’s love poems about more than heartbreak and love; they also become about having a difficult relationship with home and homeland. This understanding reveals deeper layers to poems like “Motherhood,” where the poet asks her lovers “aren’t I a home, baby?”—another question that rarely has an easy answer. Salgado’s question is not only about romance.

The way Salgado’s Salvadoran background becomes inseparable from her love life becomes inseparable from her own body image becomes inseparable from her parent’s relationship is mirrored in Lozada-Oliva’s “You Know How to Say Arroz con Pollo but Not What You Are.” In this poem, Lozada-Oliva unpacks her relationship to Spanish, and in the process, winds up narrating her parent’s romantic relationship and divorce. Lozada-Oliva ends the poem on lines about longing and distance:

i will tell you my Spanish is understanding that there are stories / that will always be out of my reach / there are people / who will never fit together the way that i wanted them to / there are letters / that will always stay / silent / there are some words that will always escape / me.

Lozada-Oliva’s Spanish is like Salgado’s mango—out of reach, escaping her. The last line break, however, implies a reversal in this relationship. My Spanish is me, the last line implies, suggesting this tangled relationship with love, language, and family history is, in fact, inescapable. Likewise, the break at “stay” implies there are words that always stay and also words that are always silent.

Don’t let these troubled relationships make you believe everything these women receive from their heritage are stumbling blocks, however. Poems like “Los Corvos” and “The Women in My Family are Bitches” showcase the strength and wisdom these poets draw from the women in their families. In “Los Corvos,” Salgado’s machete-wielding matriarchs not only become role models of physical strength, but also the emotional strength it takes to draw boundaries and let go of toxic people. “I come from women who know how to fend for themselves,” Salgado tells us. “the blade is our friend. / and you? / you are a weed. / I know how to slice you out of me.” In “The Women in My Family are Bitches,” Lozada-Oliva proudly portrays the women in her family as “cranky” and “stuck up,” but if anything, Lozada-Oliva’s reclaiming of “bitch” reconstitutes the word to make it encapsulate the women in her family in all their complexity. If the women in Lozada-Oliva’s family are bitches, they’re the bitches who ask you to “give abuelita bendiciones!” They’re the bitches who worry about you enough to ask you to pray before the plane takes off and text them before you get home. Most importantly though, both Lozada-Oliva and Salgado’s women kin believe in a self-autonomy that will cut off those who betray them.

Peluda and Corazón both show us different ways of grappling with the pressures of Latina identity. While Lozada-Oliva finds power in converting beauty regimens into rituals of resistance, Corazón traces the arc of heartbreak and demonstrates the ways vulnerability makes love possible, even after heartbreak. “all of my poems are collection plates,” Salgado declares. “I fill / and fill / and fill / and fill / and / fill / I have yet to come up empty.” If you explore these collections, reader, neither will you