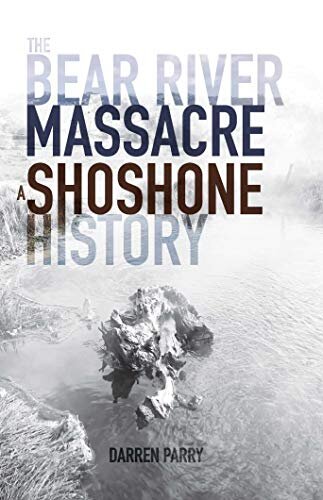

Parry begins with a chapter about his grandmother Mae Timbimboo Parry, a Shoshone historian who instilled in young Darren the importance of their cultural heritage and implanted in him the stories he shares in this book. Those wanting a critical scholarly historiography of the events should turn elsewhere. Parry’s style is much more akin to a testimony meeting than an academic essay. A six-generation Shoshone-Latter-Day-Saint, his particular perspective is both a boon and a burden to the narrative. It provides an intimacy with the material and a moral authority very few can deliver. At times, however, Parry’s own gentleness and Christlike turning of the other cheek is suffocating to someone as young and angry as me. My suspicion is that this gentleness is perfect for coaxing the fragility of non-natives and conservatives, as they grapple with the blatant injustice experienced by the Shoshone. Published by Common Consent Press, a non-profit publisher dedicated to producing affordable, high-quality books that help define and shape the Latter-day Saint experience, I hope the book finds an audience of non-native latter-day-saints ready to wrestle with the legacy of white supremacy and settler colonialism of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day-Saints. The book is extraordinarily kind to the non-native (or culturally assimilated native) reader, providing a whole chapter on what amounts to Shoshone anthropology. As a bonus at the end, Parry even includes his grandmother’s notes on traditional Shoshone food sources and uses, complete with handwritten descriptions and drawings of plants! The book strives to not just provide readers with a historical account of the Bear River Massacre, but an overview of the plight and condition of the Northwestern Shoshone. I would compare it most to The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. Du Bois in that regard. Teachers, please, this book is begging to be used as an educational text!

A hunter-gatherer civilization, the Northwestern Shoshone were largely peaceful in their interactions with the encroaching latter-day-saint settlers. Scuffles between other Shoshones/native peoples and the white settlers, however, blew back on the Northwestern Shoshone, including a November 25, 1863 attack that left two Natives and two white men dead, which served as a pretense for the massacre because racist white people can’t tell people of color apart. Even the gun-shy, Darren Parry notes, “Again, the Indian men involved were not from the Northwestern Band, but to the white authorities and settlers, Indians were Indians, and there was not much inclination to distinguish between the local Natives and those from other bands” (42). This attack, among others, led Patrick Edward Connor to eventually massacre at least 400 of the men, women, and children of the Northwestern Shoshone. Connor was a Northern commander in the Civil War sent to Utah to “protect overland routes from attacks by the Indians and quell a possible Mormon uprising” (35). Parry gives the impression that Connor was restless, eager to put his skills to use subduing Southern rebels, rather than “babysitting” the latter-day-saints. Whatever the case, because of Connor, Parry and his people were raised with stories of the massacre, of family members escaping by ingenious methods, of babies suffocated to prevent giving away their location, of many other heartrending tales Parry graciously provides.

Following the devastation of the massacre, Chief Sagwitch chooses to attempt to assimilate his people into the latter-day-saint way of life. Parry closely follows the perspective of Chief Sagwitch, the Shoshone chief responsible for converting most of his community to the LDS faith and bridging the cultural divide between latter-day-saints and Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation. So the story goes, Sagwitch received the revelation that:

“There was a time when our Father who lived above the clouds loved our fathers who lived long ago. His face shone bright upon them and their skins were white like the white man. Then they were wise and wrote books and the Father above the clouds talked with them. But after a while our people would not hear him and they quarreled and stole and fought until the Great Father got mad and turned his back on them. By doing this, He caused a shade to come over them and their skins turned black. And now we cannot see as the white man sees, because the Great Fathers face is towards him and His back is towards us. But after a while, the Great Father will quit being mad and He will turn his face towards us. Then our skins will become white.” (58-59)

Parry offers this story with surprisingly little commentary to unpack the internalized racism, anti-blackness, and white supremacy in this revelation, other than pointing out that this story fits cleanly with others from the Book of Mormon. I’m not sure what to do with this positionality yet. It is clear from Parry’s accounting that there were other voices in the Northwestern Shoshone community that felt like the Book of Mormon was only for white men (58), but their perspectives are marginalized in the text. Surely, there must be another path to the Northwestern Shoshone to remain faithful to their chosen latter-day-saint faith and still reckon with the racist attitudes of their forefathers. Thanks to Sagwitch’s leadership, however, most of the Northwestern Shoshone converted to mormonism, even if the syncretized their practices, as is common with many natives who converted to some form of Christianity.

What followed were several collaborations by native and white latter-day-saints to build a native settlement, working hard to convert a hunter-gatherer culture to an agricultural one. There are many obvious challenges to this, one of which seems to be the mismanagement by white leaders of their settlements. Parry notes that “often the Indians were only paid through food and supplies,” which usually is referred to as slavery (74). For many reasons, these settlements largely failed, harboring resentment in native communities. Despite that, natives still donated over 1000 hours to the building of the Logan temple, a fact Parry belabors in the book, and eventually built a successful community in Washakie.

In Washakie, however, the Northwestern Shoshone faced another monumental setback as after a while white latter-day-saints received orders to burn down the houses of their native neighbors while they were gone visiting family or running other errands. In the appendices, Parry includes the testimonies of many natives who lost their property, including sacred belongings in the fire. These acts of arson form another psychic wound on the Shoshone imagination that informs their current positions and outlooks.

As Parry narrates how these histories impact the present, he balances holding the church accountable with being optimistic about the ways assimilation has impacted his people. On one hand, he states, “things cannot be made right, although we should continue to [try]” (89). Lines like these show his understanding of how acute and permanent some of the damage has been. On the the other hand, he states, “Through assimilation, we have been blessed.” This quote follows another anti-black quote about God making native skins dark because of their sin (90).

My own indigenous Salvadoran ancestors likely took the route of cultural assimilation as well, after La Matanza of 1932, where over 30,000 indigenous peasants were massacred. After the killings, indigenous peoples frequently abandoned their traditional ways of dressing and their language. The pain of these massacres is still palpable in the Salvadoran cultural imagination and is one of the many factors leading to the Salvadoran Civil War. I mention this because I want to be clear in stating that I am not judging Sagwitch or his community for making the decisions they needed to in order to survive. The duty of the surviving generation, however, is to heal and reckon with the full weight of the past. The Bear River Massacre is a great first step in that direction that will hopefully open the door to more radical and diverse perspectives within the Native community.

On page 53, Parry includes (and critiques) the text of a plaque that still stands in Franklin County monument site that reads, “Attacks by the Indians on the peaceful inhabitants of this vicinity led to the final battle here on January 29, 1863….” Such a disgusting revision of history still lives in many Utah schools and communities. May Perry’s book bring us a step closer to listening to the voices of those murdered that January day.

I recommend this book for anyone interested in Native American history, American history, and creative non-fiction.